- Home

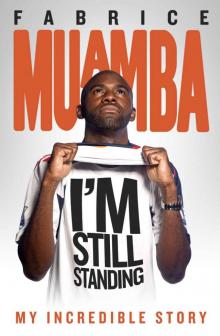

- Fabrice Muamba

Fabrice Muamba: I'm Still Standing Page 3

Fabrice Muamba: I'm Still Standing Read online

Page 3

“I’m not Fabrice anymore – please don’t call me that,” I said. “Call me Henry.” We were always doing stuff like that. Some of my mates would tell their mums to not call them by their names at all, demanding to be called Zidane or Pires or Anelka.

During the holidays I would be out of the door before seven in the morning and would get back at seven or eight at night. Mum knew she couldn’t keep me in the house or around the place so would give me some money to get food while I was out.

We’d play and play and I’d use all my money on Fanta. I’ve never been a big eater so it all went on drinks with a bit of bread every now and then. Even now, when I taste Fanta it takes me back to those times and the great memories I had of being an innocent kid just kicking a ball – and maybe even a Telstar – about.

#####

The ball drifts behind our goalkeeper Adam Bogdan’s net for a goal-kick. Bogdan waits. The ball passes from his right to his left hand as he weighs up the situation. He pats his chest and raises a gloved palm to a team-mate. Wait. The goal-kick will have to wait. Something is not right. His eyes focus upfield where I lie on the grass, eight yards from the halfway line.

Dead. For 78 minutes, I won’t be here. How do I even begin to tell this story?

Bale jogs back and glances over to this shape on the floor. I’m face down on the turf. The floodlights illuminate the white number 6 on the back of my black top. The studs of my boots can be seen as I lie with my legs apart, just as I’ve fallen. My left arm is tucked underneath me, my right almost rooted in the turf. People start panicking big time.

#####

The opening chapters of my life made me the man I am today. They gave me the values I carry forward into every area of my life, they are my inspiration and so much of what I now do is based on what happened when I was young.

Although most people think I was born in Kinshasa in the Democratic Republic of Congo, I was actually born in Lubumbashi in the south-east of the country. When I was born, in April 1988, the country was still officially called Zaire. It would change its name in 1997 following a nightmare time that would leave me and my family scared for our lives.

When people think of Africa and Africans many believe life is just one long, tough grind. There is always a ten-mile walk for water, or huge famine or poverty. That is how the story goes. While that is true for far too many people, there are also families who live normal, happy and prosperous lives. And we were definitely one of those.

Along with my mum, Christine, and dad, Marcel, I can honestly say that the early years of my life in Congo were as risk-free, relaxed and as enjoyable as living anywhere else on the planet.

We moved to Kinshasa when I was two because of dad’s work. Kinshasa is the capital of Congo and back then it was ok. It wasn’t anything like Europe but it was where I belonged and learned so much. It was a place that allowed me to spend time with my family and friends, a place where I could grow up – and play endless games of football – in peace and happiness. Or so we all thought.

We lived in a big house in a nice neighbourhood. It was a one-level property but there were about five bedrooms. It was spacious and an enjoyable place to live. The weather was usually nice and hot, it didn’t rain too much and I was like any young African boy – obsessed with the outdoors and sport.

I absolutely loved school. So many kids went to it that the day was split into two – the early pupils and the afternoon pupils. I would go until midday before the other set of kids arrived for lessons between 1pm and 5pm. It was a long day for the teachers but the place was wonderful, if a little scary at times.

Unlike England where kids attend school from a really young age, I didn’t start going until much later. I was either seven or eight when I began formal education and that allowed me to play and to learn about life and to spend time with my family. Rather than being in a classroom from the age of five onwards, I was with my family and that was so important.

I was a decent kid and just tried to keep my head down. It was completely different to school in the UK. The teachers were so strict. If you didn’t do your homework, it was time to prepare for a full-blown rant. In England you get the chance to say “sorry Miss, I forgot it” but if you tried to pull that stunt in Congo then the teachers would tear into you in no time at all. And if you skipped school then not even God himself could save you.

That was just the African mentality – work hard, be disciplined, do your classes and your homework. If you didn’t do them or you were stupid enough to ignore a teacher or show them disrespect then they would bring your whole world crashing down and it wasn’t pretty. Who wants to spend all night doing homework anyway? Get it done quickly and then go and kick a football around with your mates. That was my thinking anyway.

My teachers gave me the discipline and drive needed to help me improve while respecting my elders and being faithful to God. I mainly studied Maths, Geography and French. I spoke Lingala at home and I could’ve chosen to learn English but I picked French instead – what a life-changing decision that would turn out to be...

Mine was a fee-paying school and I was brought up knowing that it was a privilege to go to such a great place. It was a wonderful experience and it allowed me to study hard. It sorted out the building blocks of my life. Not every kid can go to a good school – it’s no different than England in that way.

Everybody called me by my nickname Fala. Everyone knew me, everyone knew Fala, the guy who likes to smile. I liked getting on with everyone, I would try and mix with my whole school. I didn’t need a best friend, we all just got on. In Congo, if your dad worked for the government like mine did, some kids would carry themselves like they were something but not me.

There was only one person I respected and feared more than the teachers and that was dad. Thank God I never got into trouble in the classroom! If news got back home that I wasn’t doing my homework or had been disrespectful to an elder I think I would have run away. I would have been too scared to go through my own front door.

Dad is quite tall and a big broad, stocky man. He is very quiet but when he says something it stays said. He speaks his mind while being laid back at the same time. I love and admire him massively. He was and is a wonderful father but he was also a strict disciplinarian.

It is an African way to show your mother and father respect and to conduct yourself in the right manner. I used to get the odd clip around the ear if I did step out of line but generally when dad said something he only had to say it once.

With dad being away most of the time with work, me and mum formed a special bond. Mum is down to earth, mellow and relaxed. She knows how to speak to everybody. Mums run the house all over the world and mine is the same. She is the boss lady – a woman with a kind heart. It was great to feel so much love coming from one person. Yes she was a tough, strong woman but her love was there for everyone to see and I felt it from such an early age.

I was an only child but there were so many family members coming in and out I didn’t really notice that. Our house was always open and there was never a day when it was quiet and dull. I really liked that although sometimes a bit of peace would have been nice! But it’s better to have too much love and too much family rather than none at all.

My early childhood was full of laughter and love. You can’t ask for any more. Growing up in Kinshasa was interesting, varied, full of sunshine and laughter. One of my early memories is of me sitting in the kitchen watching mum prepare rice and peas – the African way of cooking them both separately before combining them – and thinking how lucky I was to be going to a good school with two parents who loved me. Not everyone gets that. Maybe I was living a dream and, as with all dreams, that would have to end at some point. And it did when dad, the most influential man in my young life, suddenly had to leave the country overnight.

#####

‘GET ON THE PITCH! GET ON THE PITCH! GET ON THE PITCH!’

Andy Mitchell, our physio, has arrived from nowhere and is screaming do

wn his microphone to Dr Tobin. All thoughts of a wonderful White Hart Lane adventure are forgotten. Mitch has been looking in my direction as I fall.

He knows straight away. The way I don’t try to stop myself from butting the turf is all the evidence he needs to see that this is a bad one.

Forget waiting for referee Howard Webb to give consent, Mitch is up and running in no time at all. He is kneeling over me, his head close to mine, inspecting me, looking for signs of consciousness. Something is not right.

This is no ordinary injury. The orange stripes on the boots of Nigel Reo-Coker, are inches from my face as he stands over me, hands on hips, concerned. Spurs’ Rafael van der Vaart, William Gallas and Louis Saha are there as well.

Peter Fisher, a London Ambulance Service-trained paramedic, is a Spurs fan like Dr Tobin.

He spends matchdays working for X9 Services, a private ambulance company who provide on-field medical care when Spurs are at home. During the week he works for the London Ambulance Service full-time and they also have their own staff at the ground today. Everyone knows Peter. He’s part of the furniture.

He’s never been needed for anything serious in his five years on the White Hart Lane sidelines.

Not yet...

He sits to the left of the Spurs dugout. Close enough to see the polish on Harry Redknapp’s shoes, close enough to hear Joe Jordan shouting instructions.

Close enough to see me collapse.

As I lie on the ground, Wayne Diesel, Spurs’ head of medical services, also knows exactly what he is seeing.

“Pete, get on,” he shouts before Peter utters the words he never thought his brain would form or his mouth would speak.

“He’s dead Wayne,” he responds, racing out of his seat, picking up the stretcher with the help of his X9 colleagues.

“That boy is dead.”

#3

Leaving

SHAUNA is more than happy to keep Joshua occupied with the TV. She knows how important this match against Tottenham is, how much I want to use the FA Cup to prove to the gaffer that I deserve a place in his Premier League plans after being dropped. She loves watching me play apart from the tackling. She hates how I fly in and thinks I’m going to injure myself.

It’s a late kick-off but that’s not the end of the world. Shauna sits in her pyjamas, as does Joshua, and thinks about cooking me salmon and pasta when I arrive back home later this evening.

It’s a horrible night and she’s settled in and has no plans to go anywhere. She sips her tea and nibbles on a slice of toast. As she brushes the crumbs off her lap she takes her eyes off the telly. When she looks up she sees me lying on the grass. That slice of toast is the last thing she will eat for three days.

On the pitch, Mitch continues checking me. This is definitely no ordinary injury. He reaches under my midriff and attempts to lift me over, to perform a ‘log-roll’ procedure. I can’t be turned. He tries again, and Reo-Coker attempts to help. It is not easy, I am unresponsive.

About 120 miles away, my agent Warwick Horton is on the couch at home. He’s knackered. He’s been watching Aston Villa Under-18s play Crystal Palace earlier today and isn’t in the mood for the comedy club night he is heading for with his wife, Suzanne, in Birmingham city centre. He kicks his shoes off and just wants to watch the match, ignoring the calls from upstairs to have a shower and get ready. He convinces his wife to let him see the game until half-time so he can see how I’m doing. Plus the couch is comfortable. Not for long.

“Suzanne,” he shouts. “Come downstairs.”

“Why?” comes the response.

“Just come down here quickly,” Warwick replies.

And she does. And she bursts into tears on the spot.

#####

Before I could even point to where England was on a world map, I’d already lived a life that was perfect for a novel. It read like a spy thriller.

President Mobutu had been the leader of Zaire since 1965 and was responsible for bringing Muhammad Ali and George Foreman to the country for the ‘Rumble in the Jungle’ classic in 1974. He was a president who still divides opinion and who eventually had to flee the country himself in 1997 as he became hunted by rebel forces. He was also the man that dad called ‘Boss’.

Dad was an adviser to the president and was one of his most trusted helpers. He travelled with him everywhere. I knew dad must have been important as he went to work in a suit while all my uncles went to work in just a shirt. I remember noticing that and thinking ‘my dad must do something different’. There was no doubt about that. One of the reasons I could afford to go to a good school was because dad was well paid by the government.

When I was about seven we began to hear about trouble in the east of Congo. There was always trouble in nearby Rwanda and it started to spill over the border. But what did that mean to a tiny boy obsessed with football? It didn’t really bother me and my parents didn’t seem too worried about it either. That would soon change. Life in Kinshasa was safe and enjoyable and we expected it all to settle down and the trouble to go away. In fact, it had only just started.

Dad’s links to the president would eventually leave me without a father for five years and would leave me and mum in a state of constant worry and fear.

By the mid-1990s, President Mobutu was a deeply unpopular man in parts of the country and that led to the rise of a man called Laurent-Désiré Kabila who had plans to take control. I don’t know too much of the detail but I do know that when the new regime was trying to get power they were targeting everyone around the president.

That meant that my dad was in serious danger.

Kabila wanted President Mobutu dead and he managed to get loads of different politicians and mini-armies to unite and target the president. Marcel Muamba’s name was also on the wanted list.

If he hung around he was a dead man.

It was a bit like a football team really. When a manager is sacked and a new regime comes in, all of his old supporters are sacked with him. The only difference in this case is that dad would’ve been killed. That is Africa for you.

I remember the day he left so clearly. Losing your dad is hardly something you’re going to forget in a hurry, is it? It was a bright Sunday afternoon and he just said “I’ll see you soon.” That was it. I had no idea he was fleeing the country, going for good, saving his own life.

I thought he was just going away on business as usual. There were no tears from him or me. Why would I cry? I thought he’d be back soon, the same as always.

Mum didn’t say anything either. After five or six days, however, I realised that this wasn’t normal. “Why hasn’t he come back?” I asked mum, sensing that I was about to hear bad news.

“Your dad’s in danger,” she said. “He has had to go to another country.”

Can you imagine the confusion that caused? I was so young and naïve and didn’t know what she meant. Mum tried to explain the situation and told me that people wanted to take over from the president. Nothing really sunk in. I couldn’t work out why dad had left.

Dad’s exit also meant the end of my parents’ relationship. Mum and dad had grown apart due to the pressure they were under and that meant that when dad left his son on that day, he also left his marriage.

I say ‘marriage’ but in fact, I don’t think there is an official form of marriage in Congo. There is no regulation or paperwork. Mum wore a ring and they were together but there was no formal divorce because there was no formal marriage in the first place.

Some children go mad when their parents split up but mum wouldn’t allow that. She made me go to school, she forced me to be brave and to try and forget dad’s departure. I suppose, looking back, she was trying to protect me from the harsh truth that both our lives were now in massive danger too.

We were on the verge of death.

It wouldn’t have taken five minutes for the new regime to trace dad’s footsteps back to us and then who knows what could have happened? We lived in constant fear.

At any moment of the day or night we knew that men could snatch us, hurt us and even kill us because of dad’s old job. We kept a low profile for a very long time. I still attended school and kicked a football around but we had to stay quiet. To be seen was to be killed.

It was tough. Every child needs his father and I was no different. You need a dad to be around the house; to be there as a figurehead; to provide strength and discipline.

It meant that mum now had the jobs of two parents – and she was unbelievable. She did so well despite the turmoil going on around her. Mum’s unconditional love and strength was incredible and we became so close.

But we never forgot that there could be a knock on the door at any time. That was always on my mind.

There were regular reminders of what could happen to us. On one occasion, they targeted a couple of dad’s friends. They went straight through their front door, took everything they wanted and kicked them out. They didn’t kill them but they ruined their lives. So we lived on the fringes and in the shadows. Nobody knew we existed. Not everybody survived.

I remember waking up one day and hearing crying in the lounge. Big crying. I walked in and mum and the rest of the family were weeping loudly. In Congo, when somebody dies you cry and mourn for a full day, then the body is brought into the house the next day and there is an open coffin for people to say goodbye before they are buried the day after.

I got up from bed and asked what happened. Somebody told me that my Uncle Llunga had been killed because the new regime found out about his links to dad. He had been taken outside and shot. President Mobutu had angered a lot of people and they were coming to gain their revenge.

That summed up how close we were to becoming victims of the uprising. We were living on the edge.

They accused my uncle of hiding dad ahead of his exit from Congo and that alone was enough to murder him. It is difficult to talk about. Me and dad have never really discussed it. It is too painful for the pair of us.

When I heard my uncle had been murdered it was just too stunning to believe. The shock was incredible. Mum was very emotional but once again she had to keep it together. I heard her crying all the time. She would weep in her room when she thought I couldn’t hear her or in the day when she thought she was on her own. It was a bad time.

Fabrice Muamba: I'm Still Standing

Fabrice Muamba: I'm Still Standing